If you’ve been following my blogs, and specifically have

read my earliest posts, you know that I have no qualms pointing out my own

deficiencies …. today I admit that history has never been a strength for me but

as I get older (and older …. and older) I am more and more fascinated with

learning history – particularly the histories of England and France …. (I

better be studying French history, it will be part of the test for

citizenship!) ….. So, another confession – although I knew the basics about Napoléon

(Bonaparte) : short (nope, he wasn’t, he was the average size for the times);

exiled to Elba (yep); and the poster boy for narcissism (not sure – the juries

out on that one) ….. What I didn’t ever know, until I moved to here to France,

was that there was a Napoléon I (Bonaparte) and a Napoléon III …..both were

“Emperor(s) of the French” and boy was I confused until I realized they were

two different people (although related) ….

Napoléon

I, the Great (Emperor of the French, 1804 – 1814 and 20 March – 8 July 1815)

(Napoléon Bonaparte; Napoléon I)

Born "Napoléone di Buonaparte" (15 August 1769

– 5 May 1821), in Corsica to a relatively modest family from the minor

nobility, was a French military and political leader who rose to prominence

during the French Revolution and led several successful campaigns during the

French Revolutionary Wars. As Napoléon I, he crowned himself Emperor of the

French from 1804 until 1814, and again in 1815. Napoléon dominated European and

global affairs for more than a decade while leading France against a series of

coalitions in the Napoléonic Wars. He won most of these wars and the vast

majority of his battles, building a large empire that ruled over continental

Europe before its final collapse in 1815. One of the greatest commanders in

history, his wars and campaigns are studied at military schools worldwide. Napoléon's

political and cultural legacy has ensured his status as one of the most

celebrated and controversial leaders in human history.

The French Revolution began 1789 and Napoléon rapidly

rose through the ranks of the military, becoming a general at age 24. At

age 26, he began his first military campaign against the Austrians and their

Italian allies—winning virtually every battle, conquering the Italian Peninsula

in a year, and becoming a national hero. In 1798, he led a military expedition

to Egypt that served as a springboard to political power. He engineered a coup

in November 1799 and became First Consul of the Republic. His ambition and

public approval inspired him to go further, and in 1804 he became the first

Emperor of the French.

The Allies invaded France and captured Paris in the

spring of 1814, forcing Napoléon to abdicate, signing the “Act of Abdication”

on 11 April 1814 at the Château de

Fontainebleau.

(Abdication table; Château de Fontainebleau )

He was exiled to the island of Elba which he escaped

from in February 1815 and took control of France once again. The Allies

responded defeating Napoléon at the Battle of Waterloo in June. The British

exiled him to the remote island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic, where he

spent the remainder of his years. His death in 1821 at the age of 51 was

received with surprise, shock, and grief throughout Europe, leaving behind a

memory that still persists.

In 1840, King Louis Philippe I obtained permission from

the British to return Napoléon's remains to France. On 15 December 1840 a state

funeral was held. The hearse proceeded from the Arc de Triomphe down the Champs-Élysées,

across the Place de la Concorde to

the Esplanade des Invalides and then

to the cupola in St Jérôme's Chapel,

where it remained until the tomb designed by Louis Visconti was completed. In

1861, Napoléon's remains were entombed in a porphyry stone sarcophagus in the

crypt under the dome at Les Invalides.

(Napoléon I tomb; Les Invalides)

Napoléon had an extensive and powerful influence on the

modern world, bringing liberal reforms to the numerous territories that he

conquered and controlled, such as the Low Countries, Switzerland, and large

parts of modern Italy and Germany. He implemented fundamental liberal policies

in France and throughout Western Europe. His legal achievement, the Napoléonic

Code, has influenced the legal systems of more than 70 nations around the

world. British historian Andrew Roberts stated, "The ideas that underpin

our modern world—meritocracy, equality before the law, property rights,

religious toleration, modern secular education, sound finances, and so on—were

championed, consolidated, codified and geographically extended by Napoléon. To

them he added a rational and efficient local administration, an end to rural

banditry, the encouragement of science and the arts, the abolition of feudalism

and the greatest codification of laws since the fall of the Roman Empire.”

The Napoléonic code was adopted throughout much of

Europe, though only in the lands he conquered, and remained in force after Napoléon's

defeat. Napoléon said: "My true glory is not to have won forty battles ...

Waterloo will erase the memory of so many victories. ... But ... what will live

forever is my Civil Code." The Code influences a quarter of the world's

jurisdictions such as that of in Europe, the Americas and Africa.

Napoléon directly overthrew feudal remains in much of

Western Europe. He liberalized property laws, ended seigneurial dues, abolished

the guild of merchants and craftsmen to facilitate entrepreneurship, legalized

divorce, closed the Jewish ghettos and made Jews equal to everyone else. The

Inquisition ended as did the Holy Roman Empire. The power of church courts and

religious authority was sharply reduced and equality under the law was

proclaimed for all men.

Additionally, Napoléon instituted various reforms, such

as higher education, a tax code, road and sewer systems, and established the Banque de France, the first central bank

in French history. He negotiated the Concordat of 1801 with the Catholic

Church, which sought to reconcile the mostly Catholic population to his regime.

It was presented alongside the Organic Articles, which regulated public worship

in France. He dissolved the Holy Roman Empire prior to German Unification later

in the 19th century. The sale of the Louisiana Territory to the United States

doubled the size of the United States. In May 1802, he instituted the Legion of Honour, a substitute for the

old royalist decorations and orders of chivalry, to encourage civilian and

military achievements; the order is still the highest decoration in France.

There are critiques of Napoléon. In the political realm,

historians debate whether Napoléon was "an enlightened despot who laid the

foundations of modern Europe or, instead, a megalomaniac who wrought greater

misery than any man before the coming of Hitler." Many historians have

concluded that he had grandiose foreign policy ambitions. The Continental

powers as late as 1808 were willing to give him nearly all of his gains and

titles, but some scholars maintain he was overly aggressive and pushed for too

much, until his empire collapsed.

Napoléon institutionalized plunder of conquered

territories: French museums contain art stolen by Napoléon's forces from across

Europe. Artefacts were brought to the Musée du Louvre for a grand central

museum.

Critics argue Napoléon's true legacy must reflect the

loss of status for France and needless deaths brought by his rule: historian

Victor Davis Hanson writes, "After all, the military record is

unquestioned—17 years of wars, perhaps six million Europeans dead, France

bankrupt, her overseas colonies lost." McLynn states that, "He can be

viewed as the man who set back European economic life for a generation by the

dislocating impact of his wars." Vincent Cronin replies that such

criticism relies on the flawed premise that Napoléon was responsible for the

wars which bear his name, when in fact France was the victim of a series of

coalitions which aimed to destroy the ideals of the Revolution.

After the fall of Napoléon, not only was Napoléonic Code

retained by conquered countries including the Netherlands, Belgium, parts of

Italy and Germany, but has been used as the basis of certain parts of law

outside Europe including the Dominican Republic, the US state of Louisiana and

the Canadian province of Quebec. The memory of Napoléon in Poland is favorable,

for his support for independence and opposition to Russia, his legal code, the

abolition of serfdom, and the introduction of modern middle class

bureaucracies.

Napoléon could be considered one of the founders of

modern Germany. After dissolving the Holy Roman Empire, he reduced the number

of German states from 300 to less than 50, prior to the German Unification. A

byproduct of the French occupation was a strong development in German

nationalism. Napoléon also significantly aided the United States when he agreed

to sell the territory of Louisiana for 15 million dollars during the presidency

of Thomas Jefferson. That territory almost doubled the size of the United

States, adding the equivalent of 13 states to the Union

The myth of the "Napoléon Complex"—named after

him to describe men who have an inferiority complex—stems primarily from the

fact that he was listed, incorrectly, as 5 feet 2 inches at the time of his

death. He was 168 centimeters (5 ft 6 in) tall, an average height for a man of

that period.

Napoléon

III (Emperor of the French, 1852-1870)

(Napoléon III)

Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (born Charles-Louis Napoléon

Bonaparte; 20 April 1808 – 9 January 1873) was the only President (1848–52) of

the French Second Republic and, as Napoléon III, the Emperor (1852–70) of the

Second French Empire. He was the nephew and heir of Napoléon I. He was the

first President of France, elected by a 74.2 percent of direct popular votes

cast in 1848. He was blocked by the Constitution and Parliament from running

for a second term, so he organized a coup d'état in 1851 and then took the

throne as Napoléon III on 2 December 1852, the forty-eighth anniversary of Napoléon

I's coronation. He remains the longest-serving French head of state since the

French Revolution.

During the first years of the Empire, Napoléon's

government imposed censorship and harsh repressive measures against his

opponents. Some six thousand were imprisoned or sent to penal colonies until

1859. Thousands more went into voluntary exile abroad, including Victor Hugo.

From 1862 onwards, he relaxed government censorship, and his regime came to be

known as the "Liberal Empire." Many of his opponents returned to

France and became members of the National Assembly.

Napoléon III is best known today for his grand

reconstruction of Paris, carried out by his prefect

of the Seine, Baron Haussmann. He launched similar public works projects in

Marseille, Lyon, and other French cities. Napoléon III modernized the French

banking system, greatly expanded and consolidated the French railway system,

and made the French merchant marine the second largest in the world. He

promoted the building of the Suez Canal and established modern agriculture,

which ended famines in France and made France an agricultural exporter. Napoléon

III negotiated the 1860 Cobden–Chevalier free trade agreement with Britain and

similar agreements with France's other European trading partners. Social

reforms included giving French workers the right to strike and the right to

organize. Women's education greatly expanded, as did the list of required

subjects in public schools

Beginning in 1866, Napoléon had to face the mounting

power of Prussia, as Chancellor Otto von Bismarck sought German unification

under Prussian leadership. In July 1870, Napoléon entered the Franco-Prussian

War without allies and with inferior military forces. The French army was

rapidly defeated and Napoléon III was captured at the Battle of Sedan. The

French Third Republic was proclaimed in Paris, and Napoléon went into exile in

England, where he died in 1873.

Among the commercial innovations encouraged by Napoléon

III were the first department stores. Bon

Marché opened in 1852, followed by Au

Printemps in 1865

One of the first priorities of Napoléon III was the

modernization of the French economy, which had fallen far behind that of the

United Kingdom and some of the German states. Political economics had long been

a passion of the Emperor: While in Britain he had visited factories and railway

yards, and in prison he had studied and written about the sugar industry and

policies to reduce poverty. He wanted the government to play an active, not a

passive, role in the economy. In 1839, he had written: "Government is not

a necessary evil, as some people claim; it is instead the benevolent motor for

the whole social organism." He did not advocate the government getting

directly involved in industry. Instead, the government took a very active role

in building the infrastructure for economic growth; stimulating the stock

market and investment banks to provide credit; building railways, ports, canals

and roads; and providing training and education. He also opened up French

markets to foreign goods, such as railway tracks from England, forcing French

industry to become more efficient and more competitive.

Beginning in 1852, he encouraged the creation of new

banks, such as Crédit Mobilier, which

sold shares to the public and provided loans to both private industry and to

the government. Crédit Lyonnais was

founded in 1863, and Société Générale

in 1864. These banks provided the funding for Napoléon III's major projects,

from railway and canals to the rebuilding of Paris.

New shipping lines were created and ports rebuilt in

Marseille and Le Havre, which connected France by sea to the USA, Latin

America, North Africa and the Far East. During the Empire the number of

steamships tripled, and by 1870 France possessed, after England, the

second-largest maritime fleet in the world.

The rebuilding of central Paris also encouraged

commercial expansion and innovation. The first department store, Bon Marché, opened in Paris in 1852 in a

modest building, and expanded rapidly, its income going from 450,000 francs a

year to 20 million. Its founder, Aristide Boucicaut, commissioned a new glass

and iron building, designed by Louis-Charles Boileau and Gustave Eiffel and

opened in 1869, that became the model for the modern department store. Other

department stores quickly appeared: Au

Printemps in 1865 and La Samaritaine

in 1870.

Napoléon III's program also included reclaiming farmland

and reforestation. One such project in the Gironde department drained and

reforested 10,000 square kilometers (3,900 square miles) of moorland, creating

the Landes forest, the largest

maritime pine forest in Europe

The Avenue de

l'Opéra, was one of the new boulevards created by Napoléon III. The new

buildings on the boulevards were required to be all of the same height and same

basic facade design, and all faced with cream colored stone, giving the city

center its distinctive harmony.

Napoléon III began his regime by launching a series of

enormous public works projects in Paris, hiring tens of thousands of workers to

improve the sanitation, water supply and traffic circulation of the city. To

direct this task, he named a new Prefect

of the Seine department, Georges Eugène Haussmann, and gave him

extraordinary powers to rebuild the center of the city. He installed a large

map of Paris in a central position in his office, and he and Haussmann planned

the new Paris.

To accommodate the growing population and those who

would be forced from the center by the new boulevards and squares Napoléon III

planned to build, he issued in 1860 a decree annexing eleven surrounding communes

(municipalities), and increasing the number of arrondisments (city boroughs)

from twelve to twenty, enlarging Paris to its modern boundaries with the

exception of the two major city parks (Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes)

which only became part of the French capital in 1920.

Napoléon III built two new railway stations: the Gare de Lyon (1855) and the Gare du Nord (1865). He completed Les Halles, the great cast iron and

glass pavilioned produce market in the center of the city, and built a new municipal

hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu, in the

place of crumbling medieval buildings on the Ile de la Cité. The signature architectural landmark was the Paris Opera, the largest theater in the

world, designed by Charles Garnier, crowning the center of Napoléon III's new

Paris.

Napoléon III also wanted to build new parks and gardens

for the recreation and relaxation of the Parisians, particularly those in the

new neighborhoods of the expanding city. Napoléon III's new parks were inspired

by his memories of the parks in London, especially Hyde Park, where he had

strolled and promenaded in a carriage while in exile; but he wanted to build on

a much larger scale. Working with Haussmann and Jean-Charles Alphand, the

engineer who headed the new Service of

Promenades and Plantations, he laid out a plan for four major parks at the

cardinal points of the compass around the city. Thousands of workers and

gardeners began to dig lakes, build cascades, plant lawns, flowerbeds and

trees, and construct chalets and grottoes. Napoléon III transformed the Bois de Boulogne into a park (1852–58)

to the west of Paris: the Bois de

Vincennes (1860–65) to the east; he created the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont (1865–67) to the north, and the Parc Montsouris (1865–78) to the south.

In addition to building the four large parks, Napoléon

had the city's older parks, including Parc

Monceau, formerly owned by the Orléans

family, and the superb Jardin du

Luxembourg, refurbished and replanted. He also created some twenty small

parks and gardens in the neighborhoods, as miniature versions of his large

parks. Alphand termed these small parks "Green and flowering salons."

The intention of Napoléon's plan was to have one park in each of the eighty

"quartiers" (neighborhoods) of Paris, so that no one was more than a

ten-minute's walk from such a park. The parks were an immediate success with

all classes of Parisians

Napoléon III also began or completed the restoration of

several important historic landmarks, carried out for him by Eugène

Viollet-le-Duc. He restored the flèche,

or spire, of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame

de Paris, which had been partially destroyed and desecrated during the

French Revolution. In 1855 he completed the restoration, begun in 1845, of the

stained glass windows of the Sainte-Chapelle,

and in 1862 he declared it a national historical monument. In 1853, he approved

and provided funding for Viollet-le-Duc's restoration of the medieval town of Carcassonne. He also sponsored

Viollet-le-Duc's restoration of the Château

de Vincennes and the Château de

Pierrefonds. In 1862, he closed the prison which had occupied the Abbey of Mont-Saint-Michel since the

French Revolution, where many important political prisoners had been held, so

it could be restored and opened to the public

From the beginning of his reign Napoléon III launched a

series of social reforms aimed at improving the life of the working class. He

began with small projects, such as opening up two clinics in Paris for sick and

injured workers, a program of legal assistance to those unable to afford it,

and subsidies to companies which built low-cost housing for their workers. He

outlawed the practice of employers taking possession of or making comments in

the work document that every employee was required to carry; negative comments

meant that workers were unable to get other jobs. In 1866, he encouraged the

creation of a state insurance fund to help workers or peasants who became

disabled, and to help their widows and families.

His most important social reform was the 1864 law which

gave French workers the right to strike, which had been forbidden since 1810.

In 1866 he added to this an "Edict

of Tolerance," which gave factory workers the right to organize. He

issued a decree regulating the treatment of apprentices, limited working hours

on Sundays and holidays, and removed from the Napoléonic Code the infamous article 1781, which said that the

declaration of the employer, even without proof, would be given more weight by

the court than the word of the employee.

Napoléon III also directed the building of the French

railway network, which greatly contributed to the development of the coal

mining and steel industry in France, thereby radically changing the nature of

the French economy, which entered the modern age of large-scale capitalism. The

French economy, the second largest in the world at the time (behind the British

economy), experienced a very strong growth during the reign of Napoléon III.

Names such as steel tycoon Eugène Schneider or banking mogul James de

Rothschild are symbols of the period. Two of France's largest banks, Société Générale and Crédit Lyonnais, still in existence

today, were founded during that period. The French stock market also expanded

prodigiously, with many coal mining and steel companies issuing stocks.

Historians credit Napoléon III chiefly for supporting the railways, but not

otherwise building the economy.

Napoléon's military pressure and Russian mistakes, culminating

in the Crimean War, dealt a fatal blow to the Concert of Europe. It was based

on stability and balance of powers, whereas Napoléon attempted to rearrange the

world map to France's favor even when it involved radical and potentially

revolutionary changes in politics. A 12-pound cannon designed by France is

commonly referred to as a Napoléon cannon or 12-pounder Napoléon in his honor.

(St. Michael's Abbey, England)

Following the fall of the Second French Empire in 1870, Napoléon

III, his wife Empress Eugénie and their son the Prince Imperial were exiled

from France and took up residence in Chislehurst, England, where Napoleon III died

in 1873. He was originally buried at St Mary's Catholic Church, Chislehurst,

but, following the death of the Prince Imperial in 1879, the grief-stricken

Eugénie set about building a monument to her family. She founded the abbey, St.

Michales Abbey (Farnborough, England) in 1881 as a mausoleum for her husband

and son, wishing that the burial place should be a place of prayer and silence.

The Abbey included an Imperial Crypt, modelled on the altar of St Louis in

France, where the Emperor had originally desired to be buried, where Eugénie was

later buried alongside her husband and son. All three rest in granite

sarcophagi provided by Queen Victoria. The Abbey Church itself was designed in

an eclectic flamboyant gothic style by the renowned French architect

Gabriel-Hippolyte Destailleur.

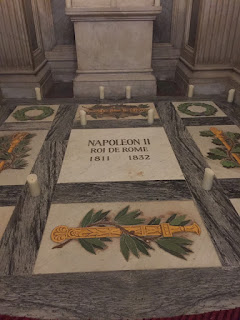

So, to answer the question that the title of

this blog asks – what happened to Napoléon II (Napoléon

II, King of Rome, “the Eaglet”) ….

(Napoléon II)

Napoléon François Charles Joseph Bonaparte (20 March

1811 – 22 July 1832), Prince Imperial, King of Rome, was the son of Napoléon I,

Emperor of the French, and his second wife, Archduchess Marie Louise of

Austria.

By Title III, article 9 of the French Constitution of

the time, he was Prince Imperial, but he was also known from birth as the King

of Rome, which Napoléon I declared was the courtesy title of the heir apparent.

His nickname of L'Aiglon ("the

Eaglet") was awarded posthumously and was popularized by the Edmond

Rostand play, L'Aiglon.

When Napoléon I abdicated on 4 April 1814, he named his

son as Emperor. However, the coalition partners that had defeated him refused

to acknowledge his son as successor; thus Napoléon I was forced to abdicate

unconditionally a number of days later. Although Napoléon II never actually

ruled France, he was briefly the titular Emperor of the French in 1815 after

the fall of his father. When his cousin Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte became the

next emperor by founding the Second French Empire in 1852, he called himself Napoléon

III to acknowledge Napoléon II and his brief reign.

(Napoléon II tomb; Les Invalides)

He died at the age of 21 and is buried at Les Invalides, along with his father, Napoléon

I.

Ç'est tout avec les Napoléons

(special credit to Wikipedia for information on the Napoléons)